Before

The Grid

The

1811 Plan

BUILDING

THE GRID

19TH-CENTURY

DEVELOPMENT

20th century–

Now

living on

the grid

other

Grids

19th-Century Development

Squares, Parks and New Avenues

As the city built the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, it also modified its form, tailoring the grid to better fit New York’s evolving needs. City officials quickly discovered that the plan had too few squares, parks, and north–south thoroughfares for a burgeoning metropolis, and over the course of the plan’s first half century, they reenvisioned the distribution of public spaces for assembly, commerce, recreation, and circulation. Most significantly, they created Central Park. Read More

In their “Remarks,” the commissioners explained that New York’s high land values had led them to curb the number of public squares and parks in their plan, believing that the city’s surrounding rivers provided sufficient open space and fresh air. The commissioners retained the small, scattered parks that had been established in the city before 1811—including Bowling Green, the Battery, and City Hall Park—and they proposed to create larger public spaces in the northern reaches of the island where land was cheaper—Bloomingdale, Hamilton, Harlem, and Manhattan Squares, and the Harlem Marsh—spaces named for local places and residents. Closer to the built-up portion of the city, they established public areas that they felt were “indispensable” and “needful”: a military parade ground, a public market, and a location for a future reservoir, which in the meantime would be occupied by an observatory. As a solution to the irregularly shaped junction of Broadway, Bowery Road, and Fourth Avenue, they created Union Place.

The current map of Manhattan has an entirely different distribution of open spaces. Many changes occurred between the late 1820s and the early 1840s, when city officials reduced or eliminated the commissioners’ planned spaces, replacing them with smaller squares established closer to the city’s population. Ornamented and landscaped, these squares served as nuclei for new, exclusive neighborhoods and were spearheaded by a blend of public officials and private individuals.

In 1827 Mayor Philip Hone established the model with Washington Square; its perimeter was quickly built up with ornate townhouses and elite institutions. In the 1830s, developer Samuel B. Ruggles replicated the formula to increase the value of his land. He created Gramercy Park (opened 1831) on his own property to serve as the nucleus of a new wealthy neighborhood. He also lobbied the city to establish Union (opened 1833) and Madison (opened 1847) Squares, among others. The city opened Tompkins Square in 1834 on cheap land below grade level. Two years later, Peter G. Stuyvesant ceded a portion of his estate to the city, forming Stuyvesant Square, directing it to be landscaped “similar to the improvement made in Washington Square.”

By the 1850s, as New York’s population and infrastructure grew denser, the clamor for more open space in New York began to influence city and state officials. In 1853 the first Central Park law was passed, introducing a new era in the city’s distribution of public space, that of large parks rather than residential squares.

Although the commissioners had envisioned an east–west city, dependent on its rivers for both work and leisure, New York became a latitudinal city, where the circulation between uptown homes and downtown workplaces dominated. In the 1830s, Ruggles initiated the effort to facilitate north–south traffic by inserting more avenues into the Commissioners’ Plan on the rapidly developing East Side, first carving the future Lexington Avenue out of his own land between Third and Fourth Avenues, inspiring the city to establish Madison Avenue between Fourth and Fifth. In 1838 the city also began retaining sections of Bloomingdale Road, now Broadway, eventually providing direct access between the east side of Manhattan and its most northern tip.

The alterations to the Commissioners’ Plan demonstrate that although Manhattan’s grid may look rigid, it actually proved flexible. The grid provided the city with an organizing principle—orthogonality—which could absorb modifications within its rectilinear structure. Show Less

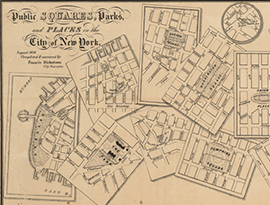

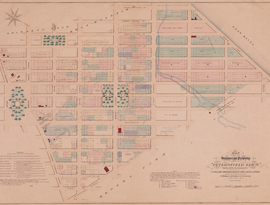

The lithograph presents a collage of scattered maps depicting all of New York’s public places in 1838. Read More

This illustration shows a mix of people gathering to watch the Seventh Regiment of the National Guard parade around Washington Square. Read More

By the 1830s Washington Square had become a fashionable residence and elegant townhouses were erected around its perimeter, some of which can be seen in this view… Read More

The Washington Square arch, an icon of New York, marks the terminus of Fifth Avenue. Read More

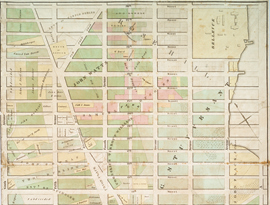

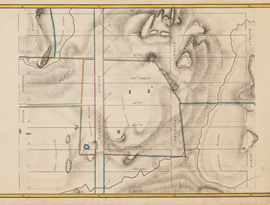

This Randel Farm Map encompasses the area bounded by Third and Sixth Avenues from 13th to 21st Street. Read More

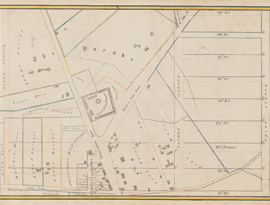

The map drawn in 1831 under the direction of city surveyor Edwin Smith overlays the pre-grid landholdings on the grid plan… Read More

Painted in 1885, this nostalgic view by Albertis Del Orient Browere imagines New York City as it was in 1828, immediately before the creation of the park. Read More

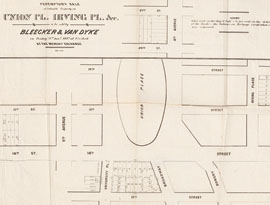

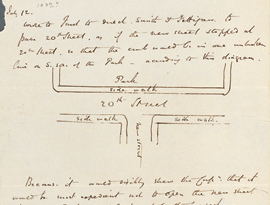

This plan records the first step in the transformation of Union Place from a triangular street intersection to a formal space with an oval lawn. Read More

Although the commissioners responsible for the grid intended New York to be a wholly American city,… Read More

This map drawn in 1868 under the direction of City Surveyor Otto Sackersdorff shows the area around Union Square in relation to the agricultural landholdings of 1815… Read More

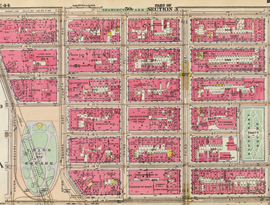

As seen in the 1916 Bromley map, Union Square had become nearly rectangular in shape, incorporating the logic of the grid in its outlines. Read More

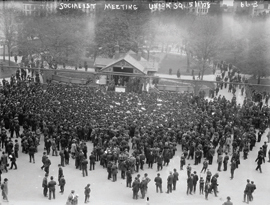

In the later 19th century and into the 20th, Union Square regularly hosted meetings of 10,000 people and more. Read More

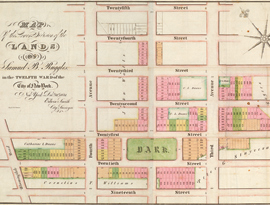

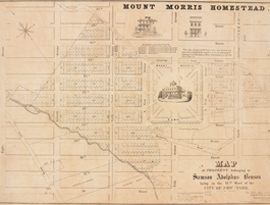

This December 1831 map of Samuel B. Ruggles’s land illustrates the developer’s vision: a rectangular green park and new avenue are central to his real estate enterprise. Read More

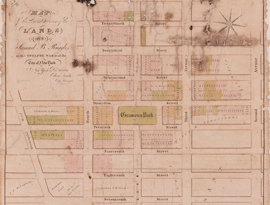

This larger scale map of Ruggles’s property shows the relationship of the Gramercy development and Union Place. Read More

Samuel B. Ruggles assembled the old Gramercy Farm through dedication and cunning maneuvering… Read More

The Panic of 1837 slowed construction of Gramercy Park, but by the late 1840s, both the economy and the neighborhood were growing. Read More

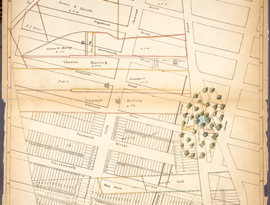

This map of property owned by the Stuyvesant family portrays Lower East Side squares that were not part of the 1811 grid plan: Union Place, Gramercy Park, and Stuyvesant.

The Society for the Diffusion of Knowledge, established in 1828 in England, published a series of inexpensive maps to educate the general public. Read More

Third Avenue runs down the middle of this Sackersdorff Farm Map. Opened in 1814 as a primary east side thoroughfare, it connected Bowery Road to the Harlem Bridge. Read More

Madison Avenue cuts a strong diagonal across this photograph taken from just south of 55th Street. Read More

With memories of the Revolutionary War and a new confrontation with England on the horizon, the commissioners deemed it crucial to provide a large space for military exercise. Read More

On April 10, 1837, an act of the New York State Legislature resuscitated the former Grand Parade as a public square. Read More

Overlooking the leafy canopy of Madison Square at left, this view south highlights two opposite approaches to the triangular lots created by the diagonal intersections of Broadway and the grid. Read More

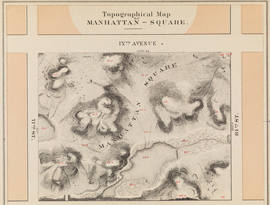

Manhattan Square was the only square envisioned by the 1811 Commissioners that retained its footprint, bounded by 77th and 81st Streets, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. Read More

Central Park was not part of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 and thus does not appear on the Randel Farm Maps of northern Manhattan. Read More

In 1853 the city used an act of eminent domain to acquire the land in the center of Manhattan for the creation of a public park. Read More

When construction began on Olmsted and Vaux’s plan for Central Park, the population of Manhattan was concentrated downtown… Read More

In his remarks on the plan for Central Park, Olmsted wrote that the most difficult problem facing the park designers was how to incorporate a transportation system… Read More

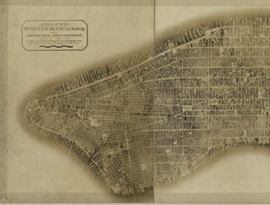

Pieced together from 100 aerial photographs, this 8-foot-long photomosaic of Manhattan demonstrates the full build out of the grid… Read More

The 1811 commissioners located Harlem Square between 117th and 121st Streets and Sixth and Seventh Avenues. Read More

The outcroppings and rusticity of the area around the Commissioners’s Harlem Square and of Mount Morris Parks is evident in this photograph of 1894… Read More

This photograph shows the old Snake Hill, the rocky landscape that led in 1836 to abandonment of the grid on this spot and its designation as a park. Read More

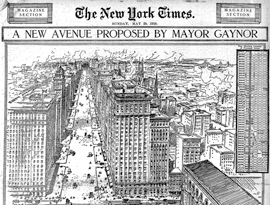

Of the various proposals sought to relieve the heavy congestion on New York’s avenues, few were as bold as Mayor William Jay Gaynor’s 1910 proposal… Read More