Before

The Grid

The

1811 Plan

BUILDING

THE GRID

19TH-CENTURY

DEVELOPMENT

20th century–

Now

living on

the grid

other

Grids

Building the Grid: From Paper to Street, Block and Lot

Opening Streets

Every public street was established in two phases: first, the city gained title over the land to open a street, and then the street was worked—regulated, graded, and paved. The city funded this public works program through a benefits and assessments system, passing on costs to adjacent property owners under the rationale that they most directly benefited from new streets in both convenience and the resultant rise in their property values.

The process of opening a street began with the street commissioner, a position established in 1802 to oversee the city’s roadways. Read More The street commissioner received petitions to open thoroughfares from property owners eager to develop their land. With a team of surveyors, he determined street grades, developed plans for improvements, and established official maps and property descriptions. He also had the power to prosecute offenders who encroached on city roads. Throughout the 19th century, when street building was a massive public works project and real estate became an important part of the economy, the street commissioner and his office held tremendous power, capable of determining the future of a proprietor’s land.

On the street commissioner’s recommendation, the city’s Common Council made the official decision to open a street. The council then applied to the state Supreme Court to appoint a Commission of Estimate and Assessment to determine assessments and benefits. The street commissioner and his men surveyed the area and rendered maps with accurate property lines. The assessment commission used the data to determine the value of the land to be taken for the street as well as how much surrounding property owners would benefit and consequently owe the city.

Proprietors were assessed multiple times: when streets were opened, when they were graded and paved, and when they were improved with sewers and perhaps new paving. The system angered landowners: they protested that the city could not take private property, that their rights were trampled, that assessments were too high, that there was little transparency, and that the street commissioner was unfair, autocratic, incompetent, or corrupt. In his 1818 pamphlet protesting the city’s system of street opening, Clement Clarke Moore colorfully described the powerlessness he felt before the Street Committee: “the owners of real property in this city are so much at the mercy of a few men, that the street-commissioner may stand on an eminence in the centre of the island, stretch out his hand, like Moses over the Red Sea; command all within the reach of his eye to be overwhelmed; and find men ready to declare publicly that they think his measures the best which could be devised.”

The system was often executed in a fraudulent and inefficient manner as city officials conspired with favorable proprietors or contractors to pay inflated sums. Critics formed the Anti-Assessment Committee, which began publishing The New York Municipal Gazette in 1841 to expose the confusing, inept, and crooked dealings of the street commissioner and “put a stop to this abominable system of ruinous assessments.”

Over time, the cost of establishing city streets became a public expense rather than one borne by local landowners. Under Boss Tweed in the 1860s and ‘70s, the city pursued an aggressive public works program, and the system of local payment through benefit assessments constrained the scale of activity. Moreover, in poor areas, improvements often lagged because of shortfalls in the benefit assessments. In 1869 the state legislature authorized a major shift in the financing of street openings and improvements: the city was permitted to fund up to half the cost of streets above 14th Street (and the full cost below) through tax revenues. The system of local assessments remained in place until 1961, when Mayor Robert F. Wagner ushered in a new city charter that included a provision to use taxes to pay for street and sewer improvements.

While street openings typically led to rising land values and photographs of newly worked streets show pristine hardscapes, streets were tumultuous, smelly, and dirty, and pigs were allowed to roam freely because they ate garbage. George Templeton Strong paints a picture in a diary entry on October 22, 1867: “Traversing for the first time the newly opened section of Madison Avenue between Fortieth Street and the College [Columbia], a rough and ragged track . . . and hardly a thoroughfare, rich in mudholes, goats, pigs, geese and stramonium. Here and there Irish shanties ‘come out’ (like smallpox postules), each composed of a dozen rotten boards and a piece of stove-pipe for a chimney.” AR Show Less

The Street Committee, the powerful group that executed the Commissioners’ Plan, is now defunct; all that remains are its masses of paperwork, the detritus of an extinct... Read More

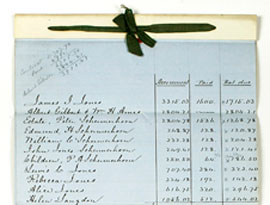

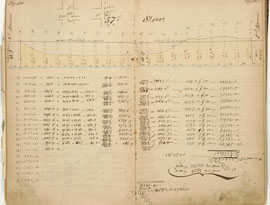

Tax collector Jameson Cox’s record book noted assessment map numbers, proprietors’ names, and assessments. Cox wrote “unknown” in cases where the city was unable to... Read More

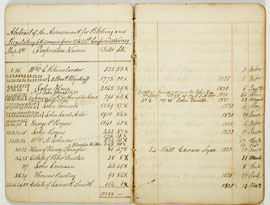

The city used this volume of colorful assessment maps to maintain records of property values and locations for tax purposes. Until the 1820s, the municipal corporation... Read More

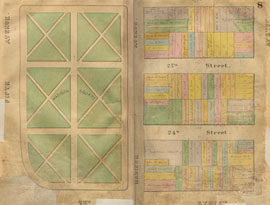

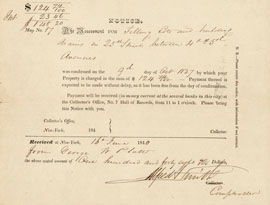

According to this receipt for a paid assessment, George Platt was charged $124.74 for filling lots and building utility pipes on 25th Street between Fourth and Fifth... Read More

The cartoon mocks the recent corruption surrounding the widening of Broadway. A well-dressed couple approaches a newspaper vendor to ask for directions: “If you please... Read More

The Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 established where the city’s future streets and avenues would be located, but it did not specify the elevation or slope at which they... Read More

In the 1830s, British visitors to New York began to remark on a “very extraordinary” and “curious” local custom: house moving. If a house stood in the way of a new or... Read More

Alessandro E. Mario presents the building of New York as an almost biblical endeavor. From an elevated vantage point looking west along 46th Street from Third Avenue... Read More

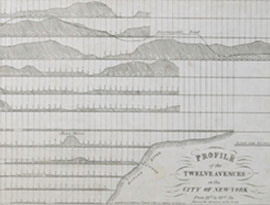

The profiles of Manhattan’s historical topography along its major avenues are shown here in a map compiled by George Hayward for Valentine’s Manual in 1850. The rugged... Read More

The topographical changes that resulted from the Commissioners’ Plan were nowhere more evident than in the view shown here of the northward path of Second Avenue on... Read More

Formidable terrain made road building on the West Side particularly difficult. By the 1860s, a horsecar could travel up Eighth Avenue only as far as 84th Street before... Read More

Grading left some lots below street level. When that happened, lot owners had to fill in their land themselves to bring their property back up to grade. For the owners... Read More

This image documents the intersection of West 84th Street and Broadway as it appeared in 1879. In the 1840s, the writer Edgar Allan Poe and his family rented a room at... Read More