Before

The Grid

The

1811 Plan

BUILDING

THE GRID

19TH-CENTURY

DEVELOPMENT

20th century–

Now

living on

the grid

other

Grids

19th-Century Development

North of Central Park: Revising the Grid

Beginning in the 1860s, the success of Central Park, the single largest change in the 1811 plan, awakened an appreciation of the city’s disappearing nature and a contempt for the uniformity of the grid. This critical orientation led to revisions of the grid in the area north of Central Park and beyond the grid’s frontier at 155th Street, where the steep hills and rough terrain deterred developers and increased the cost of building the grid.

Read More

As a result of a popular desire to reform the grid plan and the difficulty of extending it through the rugged West Side, in 1867 the state legislature gave the Board of Commissioners of Central Park the power to redesign the area from 59th to 155th Street, between Eighth Avenue and the Harlem River. Andrew Haswell Green, comptroller of the commission, took charge of the replanning effort.

A devoted public servant concerned with urban issues, Green was also a vocal critic of the grid. He faulted the 1811 commissioners for imposing a uniform plan that disregarded the island’s topographical features and failed to address issues of sewage, draining and lighting. “It is not too much to say that they . . . carried to an extreme, a system well enough adapted to the tolerably level ground of the lower part of the city,” he wrote in 1865. “The Commissioners failed to discriminate between those localities where their plan was fit, and those to which its features are destructive, both in point of expense and convenience.”

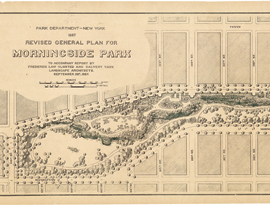

Green’s final design for the West Side largely maintained the grid, except in rugged areas that developers had avoided. Where a rocky ridge ran through the West Side, near Ninth Avenue, Green eliminated streets and established Morningside and St. Nicholas Parks. Along the Hudson River he created the long, thin Riverside Park, with an undulating Riverside Drive along its elevated eastern border. He introduced other new streets that curved along the tops of ridges, such as Convent Avenue and Morningside Drive, or that ran obliquely to the grid, such as St. Nicholas Avenue. Running up the spine of the West Side, Green laid out the broad Boulevard (later renamed Broadway).

These new parks, boulevards, and streets fed the real estate frenzy of the post–Civil War period. The boom came to a halt with the Panic of 1873, which brought about an economic recession lasting until the end of the decade. Green’s West Side improvements remained on paper until the mid-1880s.

By 1860 speculators were also pressing to develop the city north of 155th Street, where the 1811 plan stopped. At midcentury the region was home to roughly 4,000 people and accessible only by Kingsbridge Road (which extended to Spuyten Duyvil Creek) and Tenth Avenue (which ended near 190th Street). Large country villas were scattered throughout the landscape, along with Forts George and Washington and a few institutions. Northern Manhattan was mostly known for its natural beauty and rugged terrain—its salt marshes, pastures, cliffs, rolling hills, and deep valleys—elements that seemed to resist an orthogonal street plan.

The first strike against extending the grid above 155th Street came in 1860, when the state legislature passed a bill authorizing a board of seven commissioners to design a plan for upper Manhattan. The act called for a new type of plan, because it was “found impracticable, and ruinous to land owners, and injurious to the interests of the city, to grade and lay out streets and avenues north of One Hundred and Fifty-fifth street . . . upon the present plan of the city, at right angles, and in blocks of uniform size, on account of the elevated, irregular, and rocky formation of that district.” The resultant “Fort Washington Commission” planned to establish a minimal system of roads that, unlike the grid, would respond to contours of the land.

In April 1865, the legislature officially transferred the power of the Fort Washington commission to the Commissioners of Central Park, headed by Andrew H. Green, which had already earned the trust of New York’s citizens. The act gave them the power to lay out the land above 155th Street and to design a main drive from the north end of Seventh Avenue, up the Harlem River and down along the Hudson to the west entrance of Central Park at 59th Street. Green took charge of the project.

Guided by a desire to preserve the beauty of upper Manhattan, Green proposed a minimum number of roads in a layout that addressed environmental conditions and local needs. He studied the area’s climate, snow and rain fall, prevailing winds, defense requirements, sanitation, circulation, supply of water and food, and the vocations of residents. The elevated section was less developed, with compact buildings located on flatter land east of Kingsbridge, from 155th to Fort George. Because of its hilly topography, the area only supported three longitudinal avenues for moving heavy traffic—one on each shore and a third that followed the line of Kingsbridge Road. Avenues for traffic across the island would be located at each opening of the hills. Green extended the Boulevard (Broadway) from 155th Street on the highlands, rather than on the shore, in order to create a scenic drive with views.

In the end, a more developed variation of Green’s plan was built in upper Manhattan over the following 50 years, with construction on high as well as low points. Manhattan’s gridless northern arm can be read as a critique of the orthogonal island. Show Less

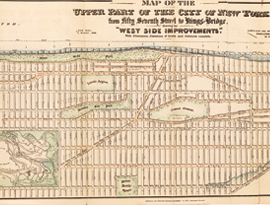

In 1868 city surveyor Hamilton E. Towle created this map to illustrate the Central Park Commission’s redesigns for the areas north and west of Central Park. Read More

The evolution of the Central Park Commission from a purely park-planning body into a comprehensive city-planning body began with a baby step. Read More

The lithograph depicts a scene on Harlem Lane, an old country road that began as an Indian trail. Read More

St. Nicholas Avenue begins at the north end of Central Park and Sixth Avenue, runs on a westward diagonal, and crosses Seventh and Eighth Avenues after it forks. Read More

This photograph looks south on the recently paved Convent Avenue, dotted with lampposts, from around 142nd Street. Read More

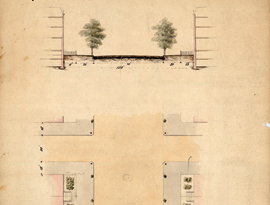

Morningside Park, just beyond the northwest corner of Central Park, is noted for its slender, elongated shape that extends from 110th to 123rd Street. Read More

This map, drawn in 1868, records an impulse to extend north of the commissioners’ original boundary line at 15th Street. Read More

Contrary to the commissioners’ expectations, by midcentury it was necessary to plan the area north of 155th Street. Read More

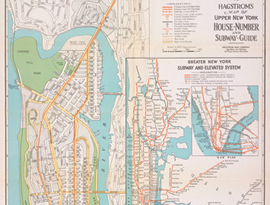

As the Hagstrom map illustrates, the northern arm of Manhattan was developed to a greater degree than Andrew H. Green had envisioned in 1868. Read More

William L. Calver’s 1914 panorama of Inwood Valley captures the landscape of the island’s northern arm, where two elevated ridges run along both coasts… Read More

Those who traveled to the upper reaches of Manhattan often described Inwood Hill as one the most picturesque areas of the city. Read More

As seen in this photograph and the next by Harlem Renaissance writer Carl Van Vechten, the upper part of Manhattan looks nothing like its leveled counterpart…

Read More

As seen in this photograph and the one previous by Harlem Renaissance writer Carl Van Vechten, the upper part of Manhattan looks nothing like its leveled counterpart… Read More

At places in the northern end of Manhattan, streets turn into steps and acquiesce to hills. Read More