Before

The Grid

The

1811 Plan

BUILDING

THE GRID

19TH-CENTURY

DEVELOPMENT

20th century–

Now

living on

the grid

other

Grids

19th-Century Development

Broadway and Its Bowties

Broadway has become a defining feature of the New York grid, yet it was not part of the 1811 plan. It was salvaged from the pre-grid landscape and assimilated with the grid. If the grid embodies a timeless, abstract order, Broadway represents history and circumstance. Read More

Broadway was the main axis of the colonial city, but it did not extend into the hinterland. It ended at about 10th Street and merged with the Bloomingdale Road, which was the primary north–south route on the island’s west side. Bloomingdale Road meandered to about 147th Street, where Kingsbridge Road took over and continued to the water’s edge. In 1811 the commissioners retained Broadway and Bloomingdale Road only up to 23rd Street, the border of the Parade. Farther north, the old roads were meant to disappear.

But Bloomingdale Road was not erased; the road remained in use and was reinstated on the map in pieces during the mid-19th century. In 1838 Bloomingdale Road was restored up to 43rd Street. It was extended to 71st Street in 1847, to 86th Street in 1851, and across the Spuyten Devil Creek to 228th Street in 1865. However, beyond 86th Street, Bloomingdale was “merely a country road, discontinuable at any time by act of the Common Council,” wrote Andrew H. Green in 1866.

The name Broadway was applied to the road below 59th Street, but in 1866 the section from 59th to 108th Street was called the Boulevard, in conjunction with a plan to widen and landscape it as a European-style promenade. In 1899 the whole long stretch was named Broadway, and the old street names—Bloomingdale, Kingsbridge, Middle, Old Harlem, and the East Post Roads—were expunged from the map. The name Broadway prevailed because it was associated with the wealth, prestige, and history of the city, which concentrated on lower Broadway. Broadway had resonance, and in keeping with the overall unity of the grid, a single name was preferred for the avenue from the bottom to the top of the island.

As each section of Bloomingdale Road was officially incorporated in the city map, it was also retraced as a straight line, whether angled or aligned with the grid, in a rapprochement with its linear logic. What makes Broadway famous is the diagonal stretch from 10th to 72nd Street; beyond that point, the avenue runs parallel with the grid. Broadway is both a relic of the past and a new artifact designed to work with the grid.

The Broadway diagonal is more than an accent that energizes the grid; it creates special urban design opportunities. There are seven intersections as Broadway crosses from Fourth to Tenth Avenue, laid out to take advantage of the wider cross streets already established by the 1811 grid. Those intersections normally yield two inverted triangles, or bowties, as they are called. Broadway begins to angle at 10th Street, and at its intersection with Fourth and Fifth Avenues, forms the only true Broadway squares: Union and Madison. Broadway then crosses Sixth and Seventh avenues (at 34th and 42nd Streets) and makes near-perfect bowties that we call Herald and Times Squares. At the intersections with Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Avenues (at 59th, 66th, and 72nd Streets), we have, in order, Columbus Circle, the inconsequential Lincoln Square, which is no more than a multilane roadway, and Sherman and Verdi Squares, better known as the entrance to the 72nd Street subway. Thereafter Broadway straightens out and loses its space-making power.

Rare are the buildings that optimize these bowtie sites and the possibility to be seen as an object in space, not only as a façade of a building tucked into a block. The Flatiron Building is the paragon: an eye-catching declaration of its triangular site. It also exemplifies the pointed, odd-shaped lots, requiring customized construction and inefficient for housing, that the commissioners sought to avoid by imposing the grid.

The Broadway intersections have also rarely been developed as great urban designs. Typically they have been treated as leftover space, occasionally decorated with an inconspicuous monument. In the past 20 years or so, the city has increasingly recognized the special character of the bowties and converted them to parks. The conversion of Broadway to a pedestrian zone under Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg has been framed as a way to optimize the traffic efficiency of the grid, but it also enhances a fundamental idea of the New York urban system: the idea of the street as public space. Think of the sea of people at Times Square on New Year’s Eve. On the one hand, this X-shaped intersection departs from the 1811 plan, and yet it epitomizes a fundamental attribute of New York urbanism that the grid brought into being: the streets are the public realm of Manhattan. Show Less

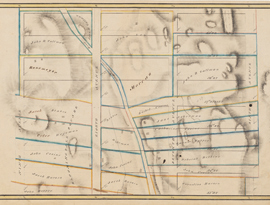

This Randel Farm Map shows the section of Bloomingdale Road between 53rd and 61st Streets, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Read More

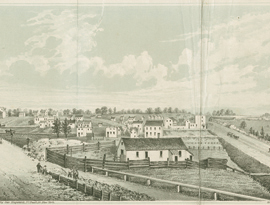

This view north corresponds to the intersection of Bloomingdale Road and Eighth Avenue at 59th Street seen on Randel Farm Map no. 29. Read More

In 1861 Benson J. Lossing described the attractive features of Bloomingdale Road: “a hard, smooth, macadamized highway, broad, devious, and undulating…” Read More

The distinctive design of the Boulevard, as the segment of today’s Broadway north of Columbus Circle was then called, is due to the urban vision of Andrew H. Green… Read More

This photograph shows the promenading life of the grand avenue, by then called Broadway. Read More

Overlooking the leafy canopy of Madison Square at left, this view south highlights two opposite approaches to the triangular lots created by the diagonal intersections of Broadway and the grid. Read More

Berenice Abbott, perhaps the greatest photographic chronicler of New York in the first half of the 20th century… Read More

The Sixth Avenue elevated train cuts right across Broadway, showing the messiness of the grid. Read More

This photograph from 1938 shows something altogether different than the previous image from 1900. Read More

This photograph does not illustrate a square at all, but a 10–block bowtie centered on the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue. Read More

Although the 1811 commissioners explicitly rejected “circles, ovals, and stars” in their plan, a circle eventually interrupted the grid. Read More

ca. 1907

At the turn of the 20th century, Manhattan street intersections in general, and Columbus Circle in particular, were choked with a dangerous jumble of horse-drawn vehicles… Read More

The ragtag look of this intersection is a visual reminder of the uneven development of Manhattan. Read More

The northernmost intersection of Broadway with an avenue occurs at West 72nd Street, where the opportunity to create a public space was exploited. Read More